The Link And The Legacy (Part Two)

WARNING This story contains elements that some readers may find upsetting (explanations of torture and historical references)

Remarkably, given the extent of the involvement of Highland Scots in the history of Guyana, their role has been all but airbrushed from history. Here is a simple test; ask someone on any Scottish street tomorrow if they know where Guyana is, or if they are aware of its importance to their own country’s industrial growth. The answer you receive will probably be ‘no’. Scotland’s role in the slave trade does not feature in schools or on the National Curriculum. Scots have generally been portrayed as reformers, abolitionists, and liberal champions. David Livingstone is remembered fondly, while the slaveowners and traders such as James McInroy, John Gladstone, Robert Allison, DC Cameron and CW&F Shand have been (until very recently) remembered euphemistically as ‘West Indian merchants’. When the National Museum of Scotland opened in 1998 it housed a huge sections devoted to ‘Scotland and the World’, without a mention of the slave trade or the slave-based plantation economy.

Scotland’s involvement in the slave trade did not begin until the union with England in 1707, however England’s participation can be traced back much further. Beginning in the last decades of the 1400s, Africans were kidnapped from their families, forced into the dark pits of especially built slave forts, and then crammed into the bowels of ships. Voyagers and traders, such as John Hawkins in the 1560s, were among the first Englishmen to amass huge fortunes from the trade in captured Africans. By the late 17th century, the British had come to dominate the slave trade, having overtaken the Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. Tens of thousands of merchant ships traversed the ‘middle passage’ across the Atlantic, in the process transforming captives from Africa into chattel goods. Half of all the Africans transported into slavery during the 18th century were carried in the holds of British ships.

Until the transportation of slaves was made illegal on British ships in 1807 more than 11 million shackled black captives were forcibly transported to the Americas. However, it is not known precisely how many arrived. Unknown multitudes were lost at sea; estimates suggest as many as two million. Slaves were often simply thrown overboard when they became too sick, too strong-willed, or food supplies onboard had begun to run low. Sharks often followed the slave ships, sensing an easy meal. Those slaves who did survive the journey were rubbed with palm oil (to make them appear healthy) and a piece of rope was forced into their rectum (to hide any signs of dysentery). They were then dumped on the shores and sold to the highest bidder, then sold or leased on, like a commodity. Mothers were separated from their children, and husbands from wives. Slaves were raped and lynched; their bodies were branded with their owner’s mark, flayed or mutilated. Demerara, where working conditions were difficult, had a particularly harsh reputation. Many slave owners, in their diaries and correspondence, freely admitted the punishments they exacted on their slaves in the sugarcane fields.

Thomas Thistlewood kept a diary for 40 years, unapologetically detailing his treatment of slaves on his Jamaica plantations during the 18th century. Thistlewood recorded 3,852 acts of sexual intercourse with 136 enslaved women in his 37 years in Jamaica. In one entry he vividly describes punishing a slave: ‘Gave him a moderate whipping, pickled him well, made Hector shit in his mouth, immediately put a gag in it whilst his mouth was full and made him wear it for 4 or 5 hours.’ If the real story of the worst excesses of British involvement in the slave trade were to be compulsory in schools, then Trevor Burnard’s brilliant study of Thistlewood’s life - Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World - should be the book that all schoolchildren read.

So just why did slavery come to an end in Demerara and other British colonies? After all, it was highly profitable for the British economy and slavery had certainly been practised in other parts of the world since ancient times. But never before had an entire territory’s economy depended on slave labour purely for the profit of capitalist industry. In 1700 Scotland was financially broke, by 1800 it was booming – all thanks to the profits of slavery.

The cultivation of sugar cane in Demerara was an intense operation. Slaves working in chain gangs in shifts that covered a 24-hour production cycle to maximise profits. In probably the greatest exploitation of expendable human labour in history, this system of plantation slavery expanded across the Caribbean, South America, and the southern United States. Fear and torture were used to drive black workers to cut, mill, boil and ‘clay’ the sugar and the plantation owners reaped huge rewards.

Often the proprietors of the plantations were known as ‘absent owners’ who spent little time in Demerara. James McInroy had returned to Scotland by 1801, certainly happy to escape the harsh climate (which took the lives of 4,000 Brits during the period). They instead employed plantation managers who returned accounts to the owners back in Britain, and reports to Parliament, in which owners and politicians alike were assured as to the smooth running of their interests in Demerara.

Any disquiet among the enslaved workers was downplayed in reports sent back to Britain, but in reality rebellion, escape and revolt where never far from the mind of the slaves. By 1800 slaves outnumbered their white masters by a factor of forty. At the head of the river, Fort William was built to a house a garrison and help enforce discipline. A gun battery, on the opposite bank of the river, kept a further eye over British interests.

Slaves, on the whole, were poorly treated in Demerara; and Christian missionaries recognised this fact, hoping to set sail and spread their gospel among the slave population. Although churches for whites had existed since the inauguration of the colony, slaves were barred from worshipping before 1807 as colonists feared education and Christianisation would lead slaves to question their status and position in the natural order of society. Indeed, a Wesleyan missionary, who arrived in 1805 wanting to set up a church for slaves, was immediately ordered to leave by order of the governor. The London Missionary Society entered Guyana shortly after the end of the slave trade in 1807, at the behest of a plantation owner who believed that slaves ought to have access to religious teachings. A 600 seat Chapel was constructed and, for a time, things improved for the slaves. Pastor John Wray arrived and spent five years in the colony. However, following the death of one of the missionaries and the departure of Pastor Wray, conditions for the slaves deteriorated quickly. They were once again subject to whipping and forced to work on Saturdays and Sundays. Plantations owners regularly broke up church services and threw stones at the chapel windows. Governor Henri Guillaume Bentinck declared all meetings after dark illegal and plantation owners did everything in their power to stop slaves attending services.

When religious instruction for slaves was endorsed by British Parliament in 1823, the plantation owners were obliged to permit slaves to attend, despite their opposition. Colonists even blocked the official written decree from the British Government, which mandated allowing slaves special passes to attend services. However, on 16th August 1823, the Governor issued a circular which required slaves to obtain owners' special dispensation to attend church meetings, which caused a sharp decline in attendance at services. Following this blatant disregard of an official instruction, the Rev. John Smith of the London Missionary Society wrote to his superiors in London:

‘Ever since I have been in the colony, the slaves have been most grievously oppressed. A most immoderate quantity of work has, very generally, been exacted of them, not excepting women far advanced in pregnancy. When sick, they have been commonly neglected, ill-treated, or half starved. Their punishments have been frequent and severe. Redress they have so seldom been able to obtain, that many of them have long discontinued to seek it, even when they have been notoriously wronged.’

- Rev. John Smith, 21st day of August 1823

The events added yet more fuel to the fire and an inevitable rebellion occurred. There had been several other minor revolts by the slaves, which had been crushed, but the Demerara uprising of August 1823 involved more than 10,000 slaves. The rebellion, lasted for just two days, and was led by slaves with the highest status. In part they were reacting to poor treatment and a desire for freedom; in addition, there was a widespread – and mistaken - belief that the British Parliament had passed a law for emancipation, but that it was being withheld by the colonial rulers. Instigated chiefly by Jack Gladstone, a slave at ‘Success’ plantation and members of their church group, including Rev. John Smith.

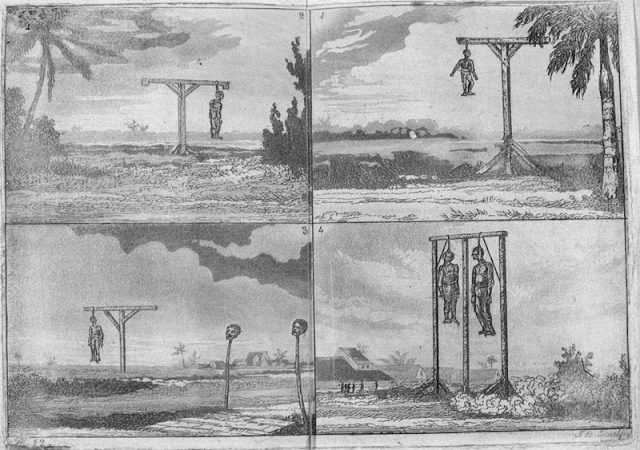

The largely non-violent rebellion was brutally crushed by the colonists under governor John Murray. Many slaves were killed; estimates range from 100 to 250. After the insurrection was put down, the government sentenced another 45 men to death, and 27 were executed. The executed slaves' bodies were left hanging on gallows in public for months afterwards as a deterrent to others (a tactic the British government had found successful in helping to crush the Jacobite rebellion 78 years earlier). Jack Gladstone was deported to the island of Saint Lucia after the rebellion following a clemency plea by Sir John Gladstone, the owner of "Success" plantation. Rev. John Smith was charged with ‘promoting discontent and dissatisfaction in the minds of the African slaves, exciting the slaves to rebel, and failing to notify the authorities that the slaves intended to rebel’. While awaiting trial he died of pneumonia in his damp prison cell. Worried that he would treated as a martyr for the abolitionist cause by the slaves, his body was quietly interred in the dead of night.

Demerara Rebellion 1823

The bodies of executed slaves were left hanging from gallows for months afterwards, as a warning to others

However Rev. Smith’s death attracted the attention of the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce in England. Smith’s case, and news of the enormous uprising and the brutal loss of African life, caused a great awakening in England, strengthening the abolitionist cause. While the Demerara Rebellion of 1823 did not appear to have been initially successful, it did help persuade the British public to switch from being pro-colonists to pro-abolition. It also led to laws changes in Demerara, creating working hours and an early form of ‘civil rights’ for slaves – which were opposed by the plantation owners.

The weekend hours were to be from sunset on Saturday to sunrise on Monday, and field work was also defined to be from 6am to 6pm, with a mandatory two-hour break. Whippings on the field were abolished, rights to marry and own property were also legalised.

However (despite the abolition of the trade in slaves in 1807) the plantations continued across the colonies. Shortly after Christmas 1831, an audacious rebellion broke out in Jamaica. Some 60,000 enslaved people went on strike. They burned the sugar cane in the fields and used their tools to smash up sugar mills. The rebels also showed remarkable discipline, imprisoning slave owners on their estates without physically harming them.

The British Jamaican government responded by violently stamping out the rebellion, killing more than 540 slaves during the fighting, and later, almost as many by firing squad and on the gallows. The uprising sent shockwaves through the British parliament and accelerated the push towards the total abolition of slavery. By 1830, debates raged in parliament, and in the public sphere, about ending slavery. The powerful West India lobby – a group of 90 or so MPs (many of them Scottish) who had ties to Caribbean slavery – opposed abolition. The faction lobbied for ‘compensated emancipation’ (the payment of money to slave owners at abolition, as a means of upholding plantation owner’s property rights). The general principle agreed by most was that, because the government paid money to landowners when it took over their fields for public works such as docks, roads, bridges and railways, it should also pay slave owners for taking over their slaves, to compensate for loss of earnings.

In the wider business community this form of compensation payment to slaveowners seemed to be viewed as the correct way to end slavery. It has also been argued, however, that slavery in the British empire was only abolished after it had ceased to be economically useful. Sugar prices had fallen and British capitalists saw fresh possibilities for profit across the globe, from South America to Australia, as new transportation and military technologies – steamships, gunboats and railways – made it possible for European settlers to penetrate new frontiers. The economic system of British slavery was moribund by 1833, but it still needed to be officially slain.

In 1833 the British Government passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which outlawed slavery in most parts of the empire (but not in Ceylon or India). To finance the slave compensation package, required by the 1833 act, the Exchequer met with International bankers Nathan Mayer Rothschild and his brother-in-law Moses Montefiore, who agreed to loan the British government £20 million to compensate aggrieved slave owners. The sum represented 40% of the government’s yearly income in those days, equivalent to some £300 billion today. To place this sum of money in context, it is £2 billion more than £298 billion anticipated to be spent by the British Government in dealing with the Coronavirus pandemic (according to the Office for Budget Responsibility), or roughly three times the current welfare budget.

In addition to huge sums of money, slave owners also received another form of compensation - the guaranteed free labour of blacks on plantations for a period of years after emancipation. The enslaved were thus forced to pay ‘reverse reparations’ to their oppressors. At the stroke of midnight on 1st August 1834, the enslaved were freed from the legal category of slavery – and instantly plunged into a new institution, called ‘apprenticeship’ or ‘indentured labour’. This arrangement was intended to last for 12 years; but was ultimately shortened to four. During this period of ‘apprenticeship’, Britain declared ‘it would teach blacks how to use their freedom responsibly; and would train them out of their natural state of savagery.’

Not a single penny, nor a single word of apology, has ever been granted by the British state to the people it enslaved, to redress the injustices they suffered. Neither has any recompense ever been offered to their descendants, or to the African countries from where more than 11 million people were kidnapped.

However, you may be surprised to learn that generations of Britons have been implicated in financing one of the world’s most egregious crimes against humanity. Almost all of us, your parents, and their parents in turn, have been paying for this huge slave-owner compensation package since the 1830s. The amount of money borrowed to finance the Slavery Abolition Act was so large that it wasn’t actually paid off until 2015. Which means that virtually every living British taxpayer unwittingly helped to finance the obscene amounts of money paid to slave traders and owners. Given the choice, we would all, no doubt, have rather the money been used to compensate the enslaved.

This information was only made public by the Treasury - in the form of a Tweet - last January, following a Freedom of Information Act request.

The legacy of Britain’s slave trade lives on. The Black Lives Matter movement and the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol are welcome moves in the right direction. However, it must be remembered that progress has been arduous, slow, and suffered many false dawns. It is worth remembering that the first black Britons were not elected to the House of Commons until near the end of the following century, more than 150 years later. Statues, buildings and street names still bare the name of Britain’s slave trading heritage. Occasionally bones of still manacled slaves have washed up on the coasts of Africa, Britain and the Americas.

Another interesting legacy of the slave trade, which I only became aware of recently, was the expression ‘on the treadmill’ – often used by people (myself included) when we wished to moan about having to return to work, or carry out a task we perceive as difficult. The Treadmill was, in fact, a punishment device, much favoured by plantation owners. This torture device, which was supposed to encourage a work ethic, was a huge turning wheel with thick, splintering wooden slats. Slaves - accused of laziness – what slave owners called the ‘negro disease’ – were hung by their hands from a plank and forced to ‘dance the treadmill’ barefoot, often for hours. If they fell or lost their step, they would be battered on their chest, feet and shins by the wooden planks. The punishment was also combined with floggings. Treadmills was actually used more in the period of ‘apprenticeships’ from 1834 onwards than before. Almost as if the plantation owners wanted to wring every last ounce of wok from their ‘apprentices’, before emancipation.

Approximately six months after Britain finally paid off its debt to all its slave owners, in 2015, then-prime minister David Cameron travelled to Jamaica on an official visit. There, on behalf of the British nation, he announced, ‘It is time to move on from this painful legacy and continue to build for the future’. One word was crucially missing from his address - ‘Sorry’.

If you are able to zoom in on this 1823 map of Demerara you can see tiny markings, indicating where the executed slaves were left to hang on especially constructed gallows

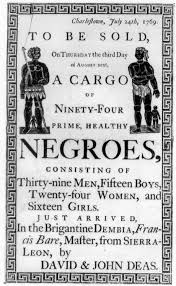

A typical slave sale poster from the era

© Copyright 2025 Mark Bridgeman Author. All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Web Smart Media