The Slave And The Slavetrader

This is the story of the rise and fall of one of Scotland's wealthiest slavetraders and the 'perpetual servant' who took on his master and, with him, the whole establishment.

John Wedderburn was born in Scotland on 21 February 1729 into a previously wealthy, but now impoverished, family. His father (Sir John Wedderburn, 5th Baronet of Blackness in Dundee), was a Perthshire gentleman who had fallen on hard times. His father's expectations of a large inheritance were unfortunately not fulfilled and he raised his nine children, including John, in ‘a small farm with a thatched house and a clay floor, which he occupied with great industry, and thereby made a laborious but starving shift to support nine children who used to run about in the fields barefoot’.

In 1745 his father joined Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Jacobite rebellion against the Hanoverian crown, serving as a colonel in the Jacobite army before being captured at the Battle of Culloden, imprisoned, then hauled off to London to face trial and execution. Indicted for treason at St Margaret's Hill, Southwark on 4 November 1746, he was subsequently found guilty, despite arguing in his defence that he had never personally taken up arms against the Crown, and was executed at Kennington Common on 28 November 1746.

Then just 17 years of age the young John Wedderburn made his way to London to plead with friends, family and the authorities for his father's rescue and pardon. Unfortunately his mission failed, and he was forced to witness his father's execution as a traitor by the brutal method of hanging, drawing and quartering. After the execution he was compelled to return to Scotland where he found himself cut off from any meagre inheritance he might have received. Without prospects, he decided to seek his fortune in the New World. On visit to Glasgow he found a ship's captain prepared to let him work his passage on a ship bound for the Caribbean.

In early 1747 John Wedderburn landed in the British Colony of Jamaica. The island had been seized from the Spanish by Cromwell in 1655 as part of his ambitious Western Expansion, and was fast becoming an important centre for the production and export of sugar. John Wedderburn initially settled in the west of Jamaica, near Montego Bay, and tried his hand at a number of occupations, even practising for a few years as a medical doctor, despite having no qualifications. Through his travails he managed to acquire sufficient capital to become a planter and invested in land, slaves and sugar. During the 18th century sugar was an immensely profitable business. The British soon became the largest producers of sugar in the world, and the British people quickly became the commodity's largest consumers. West Indian sugar became ubiquitous as an additive to Indian tea. It has been estimated that by 1900 the profits of the slave trade and of West Indian plantations accounted for one in every twenty pounds then circulating in the British economy.

Scotland had one of the highest proportion of slave owners to the general populous of any nation during the 18th century, with people in Edinburgh twice as likely to own a slave as a person in Glasgow or London during the same period. In Edinburgh, one in 1,238 had connections to plantations compared to London where it was one in 1,721 people in the city.

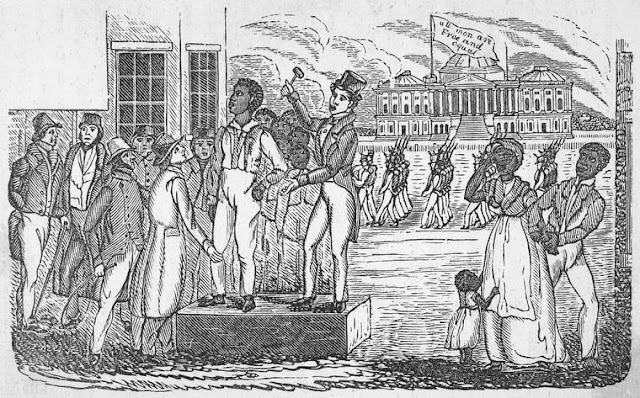

Wedderburn's sugar plantations prospered and he soon acquired huge amounts of land and wealth, becoming at one time the largest landowner in Jamaica, with around 17,000 acres of land, around 10% of the island's landmass. Other members of his family followed him from Scotland, and the Wedderburns built up extensive estates in the colony. Wedderburn took a full role in the buying and selling of slaves at the markets in Jamaica and via the published periodicals. The Royal Gazette of Jamaica carried realms of ‘small ads’ from plantation owners advertising the buying and selling of ‘negros’ and offering rewards for ‘runaways’.

In 1762 Wedderburn attended a ‘scramble’ at Farquharson Wharf in Black River and purchased a young African boy aged 12 or 13 years, named Joseph Knight after the captain of the ship that had brought him to the West Indies. Farquharson Wharf was a Scottish owned site in Jamaica at which regular slave auctions were held. ‘Scrambles’ were so-called because greedy buyers would literally ‘scramble’ to gather as many slaves as they could possibly obtain.

Rather than set Knight to work as a field hand, Wedderburn instead made him a house servant, teaching him to read and write and then having him baptised as a Christian.

Seven years later, in 1769, Wedderburn returned to Scotland, and brought Joseph Knight with him. He returned to Perthshire where he hoped to use his considerable wealth to re-establish his family's respectability, marry and raise a family. His ambition was also to reclaim the title Baronet of Blackness (lost by his impoverished father). Shortly after arriving in Perthshire he purchased the Ballindean estate, near Inchture, a village halfway between Perth and Dundee on the northern side of the Firth of Tay. Although the name Ballindean House still survives Wedderburn’s house does not. The existing property is an 1832 rebuild.

On 25 November 1769, aged 40 years, Wedderburn married his first wife, Margaret Ogilvy, daughter of David Ogilvy, 6th Earl of Airlie, in Cortachy, Angus. The couple had four children, of whom three survived to adulthood. During this prosperous and content period in Wedderburn’s life Joseph Knight continued working at Ballindean House as a servant. Knight in turn fell in love with Annie Thompson, a local girl from Dundee, who also worked on the estate. Knight asked his master for permission to marry Annie, and permission was granted.

In 1774, Joseph Knight became aware of an English Court ruling in the so-called ‘Somerset Case’, which held that slavery did not exist under English law. This famous 1772 ruling on labour law and human rights in the case (presided over by Lord Mansfield of Scone Palace), held that chattel slavery was unsupported by the common law in England and Wales, although the position elsewhere in the British Empire was left ambiguous. Perhaps assuming that a ruling in an English court would apply equally in Scotland, Joseph Knight demanded his freedom, and even asked for back wages, which Wedderburn refused. Wedderburn was furious, feeling that he had bestowed considerable gifts on Knight by both educating and taking care of him.

Soon, Annie Thompson fell pregnant with Knight's child and Wedderburn dismissed her; but refused Joseph Knight permission to leave his employment, which would have enabled him to be with Annie. When Wedderburn found Knight packing his bags to leave anyway, he summoned the magistrate and had him arrested and thrown into Perth jail. Joseph Knight was able to persuade John Swinton, the Deputy Sheriff at Perth Sheriff Court, to represent him, claiming that he should be entitled to his freedom, following the convention set in the ‘Somerset Case’. Knight therefore brought a claim before the Justices of the Peace court in Perth, a case that would be known as Knight v Wedderburn. Knight argued that the act of landing in Scotland freed him from perpetual servitude, as slavery was not recognised in Scotland. Wedderburn claimed that the fall out between Knight and himself had only occurred due to Knight’s romantic involvement with Annie Thompson.

At first, events seemed to move in John Wedderburn's favour. The Justices of the Peace found against Knight, but, refusing to accept defeat, Joseph Knight appealed to the Sheriff Court of Perth, who this time found against Wedderburn, stating that:

‘the state of slavery is not recognised by the laws of this kingdom, and is inconsistent with the principles thereof: That the regulations in Jamaica, concerning slaves, do not extend to this kingdom’.

The matter did not finish there, however. In 1777 Wedderburn in turn appealed to the Court of Session in Edinburgh, Scotland's supreme civil court. His main argument was that slavery and perpetual servitude were different states, and that in Scots law, Knight, even though he was not recognised as a slave, was still bound to ‘provide perpetual service in the same manner as an indentured servant or an apprenticed artisan’. The case was important enough that it was given a full panel of twelve judges including Lord Kames, the important legal and social historian.

Knight was surprisingly represented by no less than Henry Dundas, the Lord Advocate of Scotland, who was outraged by Knight's condition, but actually had interests himself in the slave trade. Dundas was in turn helped in the preparation of the case by the famous writers James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, who both took a keen interest, lending their considerable weight to Knight's defence. Their argument was that 'no man is by nature the property of another'. Knight argued that he had not given up his natural freedom willingly, and that he should be set free to make a home for his wife and child. Knight presented the court with a compelling 40 – page document (partly written in French) detailing his life as a slave. Conversely, Wedderburn's counsel argued that commercial interests, which underpinned Scotland's prosperity, should prevail.

In an unexpected decision, Lord Kames stated that 'we sit here to enforce right not to enforce wrong' and the court emphatically rejected Wedderburn's appeal, ruling by an 8 to 4 majority that:

‘the dominion assumed over this Negro, under the law of Jamaica, being unjust, could not be supported in this country to any extent: That, therefore, the defender had no right to the Negro’s service for any space of time, nor to send him out of the country against his consent: That the Negro was likewise protected under the act 1701, c.6. from being sent out of the country against his consent.’

In effect, slavery was not recognised by Scots law and runaway slaves (or 'perpetual servants'), if they wished to leave domestic service or were resisting attempts to return them to slavery in the colonies, could be protected by the courts.

Not at all perturbed by his defeat John Wedderburn, devoted the rest of his days to upholding the rights of slaveholders through his support of London Society of West India Planters and Merchants (an organisation formed to help resist the abolition of the slave trade and that of slavery itself). He remarried following the death of his first wife and was eventually successful in claiming the title 6th Baronet of Blackness, thereby restoring his family's respectability after the disaster of defeat and humiliation at Culloden.

Interestingly, his nephew Robert Wedderburn (who was disowned by the rest of his family) was a tireless campaigner against slavery, and published an anti-slavery book entitled The Horrors of Slavery in 1824.

John Wedderburn died a wealthy man on 13 June 1803, aged 74 years – just four years before Britain banned the Atlantic slave trade.

Joseph Knight was granted his freedom and went on to marry Annie Thompson, although little is known of their lives after the trials. His name did live on, however, as being fundamental in the abolition of the slave trade in Scotland.

© Copyright 2025 Mark Bridgeman Author. All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Web Smart Media